Thar she blows. My first-ever Blurb book. 2006(ish) timeframe. I had been self-publishing for about a decade by the time Blurb became an official thing. During this period, most of my bookmaking was relegated to handmade books or semi-handmade books printed via desktop inkjet, reprographic houses, or places like Kinkos. Nothing wrong with any of these methods, but Blurb changed my life. For the first time, I could produce a wide range of books via free software, then sell those books through a bookstore on the backend of the site.

Los Angeles is a fine city, if you like that kind of thing, but going to the post office in Los Angeles is not for the faint of heart. I once saw a guy peeing in the corner while I was standing to buy postage. I saw another man attempting to beat his child, who had crawled into a pile of abandoned boxes to avoid the beating, infuriating the father even further, before bystanders pounced on him. There was never more than one teller behind the two-inch bulletproof glass, regardless of how many teller slots the location had, and to quell the insurrection of patrons, the post office decided to install a tiny TV monitor high up near the ceiling in the hope they could show us sitcoms or documentaries which might distract us from the subpar service. When the man attempted to beat his child, I looked up to watch a lion tearing apart a gazelle on the African plains. It was so perfect. My point is, anytime you can avoid the post office, it’s a good thing. Blurb allowed me to avoid the post office.

I began to use Blurb because of the bookstore.

I not only no longer needed to visit the post office, but I could also now send clients to a link and have them purchase their books straight from Blurb. They, in turn, could send their clients to the same link to buy additional copies. I quickly turned all commercial shoots into Blurb books. (120 books) Boom. Anytime I was commissioned to do a shoot, I would automatically design and print a book, using the opportunity to brand the publications with my studio name, contact information, and website. In essence, the clients were paying for my marketing collateral. There were times when I visited a new client’s office only to see my books on their coffee table, BEFORE I had ever done a job for them.

In terms of pure print quality, there were still issues being worked out, but by then, I already knew several very important factors. One: the story is far more important than perfect color or black-and-white. My clients wanted things to look good, but good photography, good story, and good design were far more critical to a book’s success than perfect color. Two: clients didn’t hold books up to windows to see how images looked. They responded to the overall piece. Even in the early, early days, not one client ever said anything about the color or black and white being off, even when it was.

I expected things to go wrong because the technology was new and Blurb was pushing boundaries while developing a platform for people like me. Believe me, there were plenty of tantrum-loving photographers who ranted and raved about these new book companies, something that did far more harm than good. There is a reason why I was asked to be on the Blurb advisory board, and these other folks were not. I understood the challenges and rolled with the digital punches. In addition, I was using other companies that truly had issues with their products.

One company I loved, which will remain nameless even though it was short-lived and has been gone for almost fifteen years, made books that immediately fell apart. The bind would unravel, explode, unglue, etc. I didn’t care. And I still have those samples. Another Blurb alternative would print proof pages, allowing the author to check their work before printing the final book. Photographers would hold those pages in front of me and say, “See, if Blurb did THIS, I would use them.” “I would look at them and say, “Don’t get used to it, that is totally unsustainable.” Less than a year later, that company had shuttered. Another company refused to print my books after seeing a story I made about the oldest male adult film star working in Hollywood. They called me a pornographer and slammed their door in my face. (I covered this story from all angles, but could also edit a version for American editorial outlets.) The thrill of getting a book, ANY book, was so overwhelmingly positive that it far overshadowed anything negative.

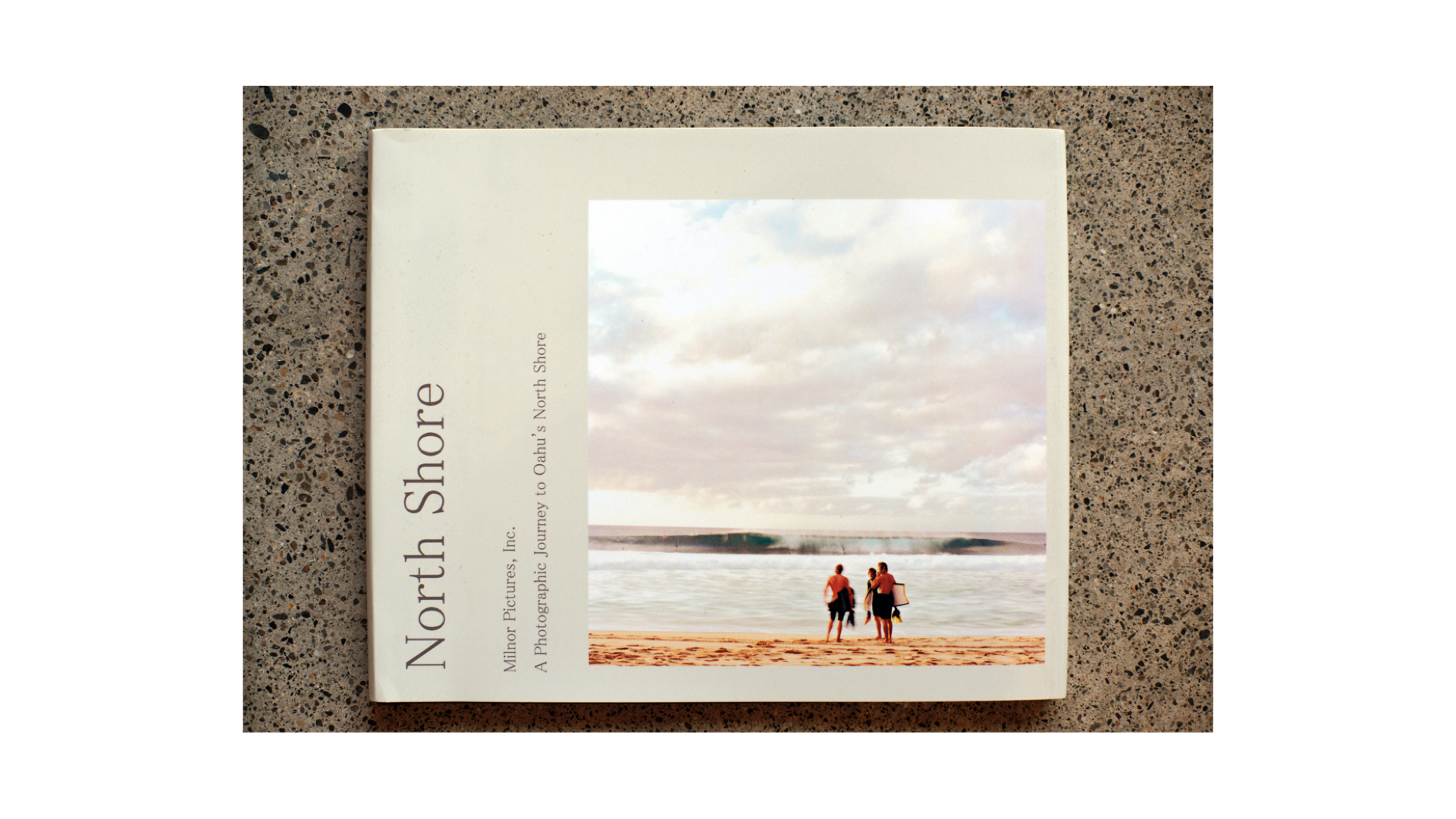

The book you see here is a test book. It is the physical embodiment of what I’ve been telling people to do for the past fifteen years. Make a test book. Although I was primarily shooting portraits when I made this book, I was also doing self-assigned documentary projects. Every December, for roughly ten years, I would venture to Hawaii to cover the Triple Crown of Surfing. This was such a great time to be a photographer and such a great series of events to cover, not to mention the unique culture of the North Shore, which made for some interesting photographs.

My wife handed me a flyer from a new company called Blurb. I had this North Shore work on my desktop, so I quickly chose some images and began to make a book. Color, black and white, toned black and white, colored pages, white pages, a bit of text, etc. My intention was not to make a good book. I intended to make a test book. I needed to know what Blurb could or could not do. I needed to see type at varying sizes. I needed to see if the cover image matched the interior photographs. I needed to see the bleed through and the paper surface. I needed to feel the overall object.

Looking at these images now brings back memories. My life was SO slow. I was shooting film, rarely ever used my mobile phone, and didn’t even bring a computer for the first few years. My hotel balcony had exposed rebar and was being torn down around us. There were only crowds on contest days. Photographers from all over the world would get together nightly to party and look at slides. The film was dropped off at the local Foodland grocery store, where it was driven to a lab in Honolulu, then driven back the next day. I smoked clove cigarettes and swam in the ocean every single day. For the next several years, this book served as a roadmap. All other books were sourced from this one. I still do the same thing today, as many of you know, after seeing the six test books from my latest voyage. Books are the source. Plain and simple. I’ve given Blurb books away, and I’ve sold them for $1500 per copy. I’ve had them collected by museums, sold in photobook and museum stores, had them collected by photobook archives, and had them exhibited in Australia, the UK, and all across the United States.

My advice to you is this. Don’t complain and don’t wait for a perfect solution to anything. You do not have time to do this. The best creatives are the ones pushing forward. They don’t draw lines in the sand. They don’t care how they look. They don’t care how they are viewed by the industry because they are always out in front, looking back at the muddled masses who are waiting for something perfect. There is no such thing.

PS: Eileen Gittins will forever be etched in the history of modern photography. She founded Blurb at significant personal financial risk, with new technology still being developed. Tens of millions of unique titles later, Blurb is still going strong.

Comments 4

Dan – a truly wonderful memory – thanks for writing and sharing. A.

Author

Hey Alex, great hearing from you. And thank you. I might still have this physical copy buried somewhere….

Your point about making test books early on and often, without getting hung up by perfectionism, is excellent! I’ve been working on adopting this practice lately and found it to be helpful with the daunting job of editing and sequencing. I just keep these test books around in my study and leisurely leaf through them from time to time. More often than not weak pictures or bad sequencing would just jump at me once my mind is no longer preoccupied with the project. It’s almost as if you could view your work through the eyes of a stranger. Viewing a PDF on the computer doesn’t work quite as well – nothing beats a real book!

Author

You summed it up perfectly. And yes, distance from a project can be significant. I left my Sicily project for two years, and when I returned to it, I could not believe what I missed the first time.